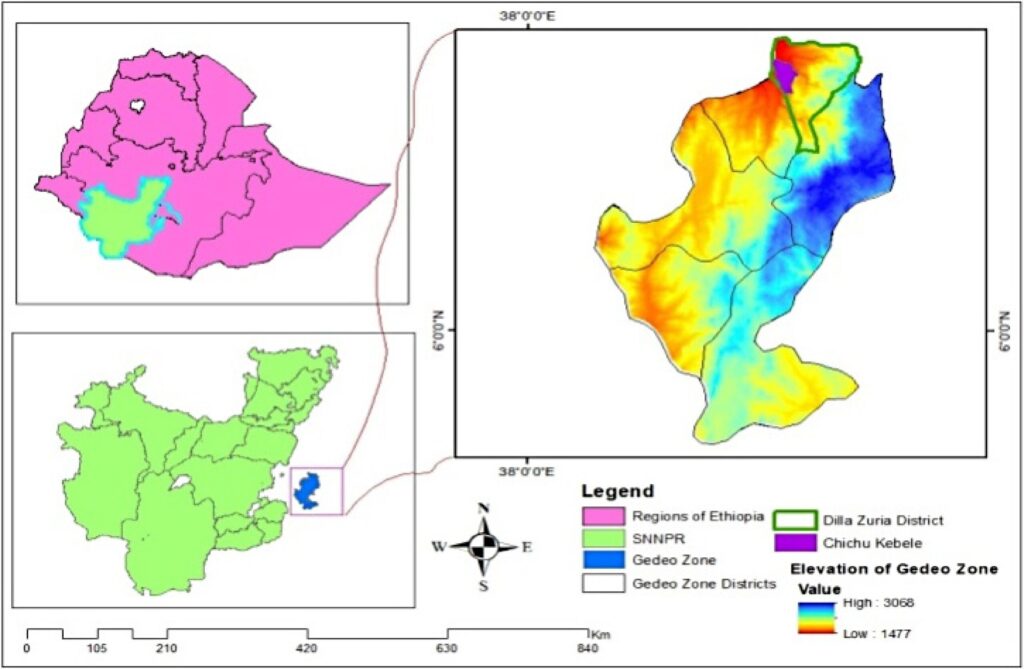

Image from Getahun et al. (2025), Beverage Plant Research (Maximum Academic Press), used under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0).

A decade of farm-level data from Ethiopia’s Gedeo Zone suggests coffee quality and yield are not dictated by a single factor such as altitude. Instead, the strongest quality signals may be traced back to multiple related factors affecting soil health, with results varying by micro-region.

The study reinforces commonly held best practices in sustainable agricultural land management — such as the inclusion of shade — while rejecting the idea of a one-size-fits-all playbook for different growing areas.

Adapting to Climate Pressure

The research, published late last year in the journal Beverage Plant Research, is framed by the growing need for climate adaptation and resilience among Ethiopian coffee farmers, with implications for producers globally.

“Climate change and variability in rainfall and temperature patterns are significantly impacting arabica coffee production, which thrives in specific climatic and topographic conditions,” the research team wrote. “Understanding these variables is essential to safeguarding Ethiopia’s coffee industry against the challenges posed by climate change.”

Focused on farm management as opposed to post-harvest processing, researchers analyzed coffee production environments across 18 rural kebeles (local administrative areas) in southern Ethiopia’s Gedeo Zone using farm records from 2013-2022, alongside topography, climate and soil data, farmer interviews and GIS tools.

Using statistics designed to shrink a long list of variables into a smaller set of “what matters most” for total coffee production, the team reports that 12 principal components explained 95.4% of the total variation in the dataset.

Soil and Clustering

In the analysis, soil cation exchange capacity — a measure tied to how well soil holds nutrients — was the largest single contributor to variation, while “evapotranspiration” and shade trees were also leading variables. Other important variables included nitrogen, altitude, ash, organic carbon, iron, soil water conservation, the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), coffee variety and soil clay content.

After identifying these variables, the research team divided the region into five “clusters” to provide more detailed analysis and recommendations at the microclimate level.

For example, at Wotiko, a highland cluster, the authors suggest improving coffee production and quality through steps including “cold and frost tolerant high land coffee varieties,” management for light capture, liming and vermin-composting options. At Dumerso, described as mid- to highland with occasional waterlogs, the research points to raised beds, drainage structures, compatible shade trees, composting schemes and reducing eucalyptus and sugarcane from coffee fields.

“The findings of this study provide practical recommendations for farmers, agricultural planners and policymakers in Ethiopia,” the research team wrote. “By understanding the specific factors influencing coffee production in each cluster, tailored strategies can be implemented to improve yield and quality.”

Funding for the research was provided by Ethiopia’s Dilla University. The authors — including Tedla Getahun, Girma Mamo, Getahun Haile and Gebremedehin Tesfaye — did not declare any conflicts of interest.

Comments? Questions? News to share? Contact DCN’s editors here. For all the latest coffee industry news, subscribe to the DCN newsletter.

Related Posts

Source link